I published “Art of my Art” on a Wordpress blog on September 4, 2013. I’m resurrecting it with some edits because it seems related to my last two posts on a new Romanticism (Romanticism and More Romanticism). Here it is:

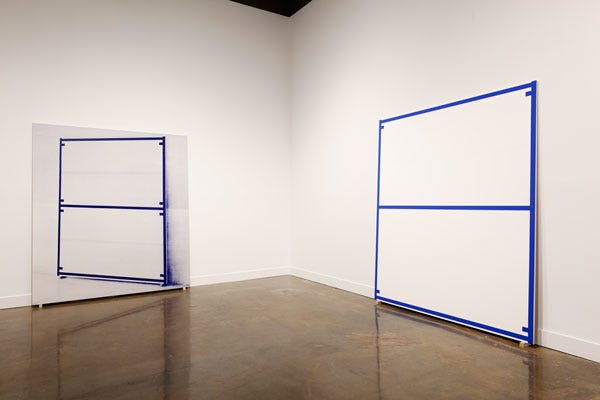

I discovered Alan Uglow thanks to an article by Gregory Williams in The Brooklyn Rail (Image courtesy of Brooklyn Rail) The painting on the right is from 1994, the serigraph “portrait” of the painting on the left, is from 2000. In my opinion, it’s not a very strong work, but it’s symptomatic of something that’s been on my mind - the strategy of copying your own work, and I don't mean for financial reasons as Arnold Böcklin did with the Isle of the Dead. There were five of those, and I previously posted them here.

This post was going to be about Uglow, Sherrie Levine, and me, and possibly Gerhard Richter as well, in an effort to examine how copying your own work could be a way forward from a number of issues facing artists. These include appropriation, the arbitrariness of subject matter, and the general flatness of everything.

Sherrie Levine has made her career as an “appropriation artist”. She came to my attention in 1981 when she rephotographed pictures by Walker Evans and showed them as her own. It was a brilliant choice because Evans was such a damned earnest photographer living in a time when artists really thought they were making a difference (aesthetic, political or both).

Levine’s move was a refreshingly bitter thing to do. It dripped with contempt, and appealed to the Oedipal complex hidden in the hearts of artists. The art world had become a smooth plain with horizons that had no distinctive features. It was difficult to find things sticking up enough to warrant sincere attention.

Then I got upset. The problem started when I searched Sherrie Levine to confirm she was the one who rephotographed the work of Walker Evans, the cleanest version of appropriation I'm aware of. That’s when I stumbled on this painting of hers, part of a series completed between 1987 and 2002. This particular one is from 1988.

So why am I upset?

I made these two plywood knot paintings in 1993, and called them The Things at the Edge of the Universe 1 and 2, 45″ x 50″ and 15″ x 26″.

So of course, they are related to the idea of appropriation and the difficulties of deciding on subject matter when all things seem equal and nothing seems worthy of saying. They are ‘found’ compositions to some extent. All I had to do was colour them in. This is the nihilism of 1980’s Postmodernism.

But there is more. My two paintings are not just about appropriation and the lack of reasons to choose. Those issues had been well covered by Warhol and Duchamp. Appropriation art was a rehash of Warhol’s superficiality coupled with Duchamp’s Readymades. I wasn't interested in just making more of the same.

These two paintings have rounded corners, mildly suggestive of cathode ray tubes, that’s what TV’s and computers looked like in 1993. The paintings are covered in scratched quarter-inch plexiglass (I re-purposed plexiglass that used to be under wheeled office chairs in carpeted cubicles). The clear but scratched top layer elevated visibility to a second, simultaneous picture plane.

I drilled an array of holes for finishing nails and the occasional screw through the plexiglass. They were arranged in a grid that was not square with the sides of the work, which gives the grid some tilt, but no perspectival vanishing point. This was intended to irritate the perceptual process of a viewer - noticing your own seeing elevates consciousness.

The nails hold the layers together, but they are also visible objects that travel through all the virtual objects generated with both the paint and the scratches. They were like wormholes, or astronomical black holes. The nails pierced the visible and held the world together. And perhaps those nails are the things at the edge of the universe referenced in the works’ titles. The more obvious, painted knots may have been a diversion.

For the most part I don’t mind obscurity, but there are times when it’s frustrating. It’s frustrating because I feel compelled to defend and explain my work when I come across things that look quite similar – plywood knot paintings for example. Thankfully, I think it’s possible to feel some schadenfreude for my own misfortune. Grimly satisfying wound licking isn’t half bad if that's the only thing available.

While flattering myself that my work measures up to his, I can easily imagine myself in the circumstances of Kurt Schwitters. He said we shouldn’t worry about his obscurity and poverty because he knew very well how important he was. And he was right, he is important – his shadow continues to grow, just as Picasso’s shrinks. Therefore, I will not be bothered by the fact that I seem to have made a career of being overlooked and underestimated.

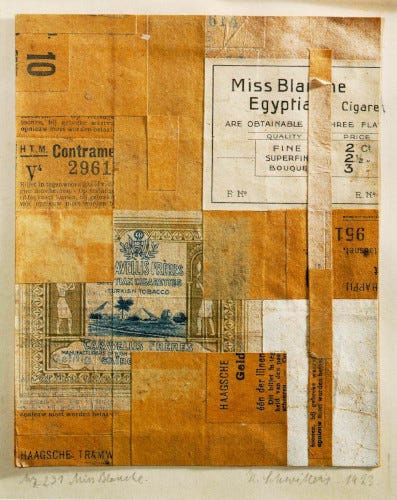

http://www.wikipaintings.org/en/kurt-schwitters/mz-231-miss-blanche-1923

Schwitters made this in 1923 – and it contains seeds of almost all the ‘retinal’ art that follows. “Retinal” is a reference to Duchamp’s pejorative term for all art that isn’t ‘conceptual’, for lack of a better word. It seems to me though, that visual art would use a retinal vehicle. It communicates through vision. And looking at this one humble collage from 1923, I know I have a lot of work to do. The insidious influence of theory still drives me, I’m not retinal enough.

Nonetheless, I’m sympathetic with appropriation, and in the 1970′s I tried my hand at it with a series of one-piece collages. From time to time, from 1976 to 1999, I tore things from newspapers, magazines, brochures, and maps that appealed to me, and I mounted them and signed them. These two are both coincidentally from 1979. I picked them because they look nice on my computer screen.

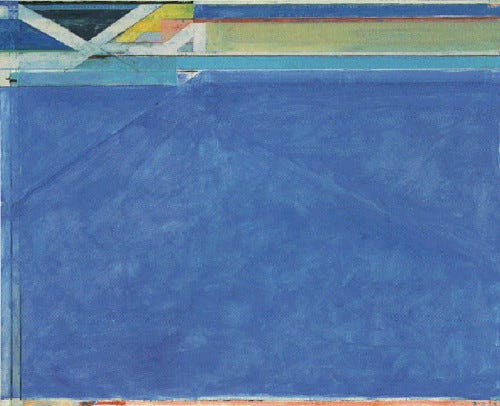

Seeing that map once again makes me think it would make a nice painting – a little bit of a Richard Diebenkorn Ocean Park Series thing going on there.

From http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Richard_Diebenkorn%27s_painting_%27Ocean_Park_No.129%27.jpg

My use of appropriation was sour grapes and mere cleverness to some extent, but it still had a hint of vicarious escape from media saturation in it. I took back the initiative and the choosing, I was less of a passive consumer. That was the do-good, Schwitters part, but that’s hardly adequate to the ambitions of art.

Appropriation is basically a rehash of Conceptual and Pop art. It is the blindingly obvious thing to do after Duchamp and Warhol. It’s also a one-trick pony to establish an art career. But as far as appropriation goes, I couldn’t be bothered with anything more than some scrap booking – there are so many other things to think about.

So much for being vexed, and onto the matter of copying your own work. I have three rules for art making: It needs charm, it acknowledges its roots in a tradition, and it contains some other idea - hopefully a new way to see or understand something. That’s a tall order, and I know I don’t always succeed.

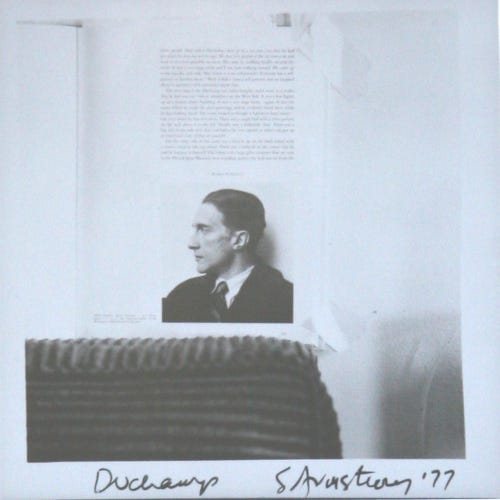

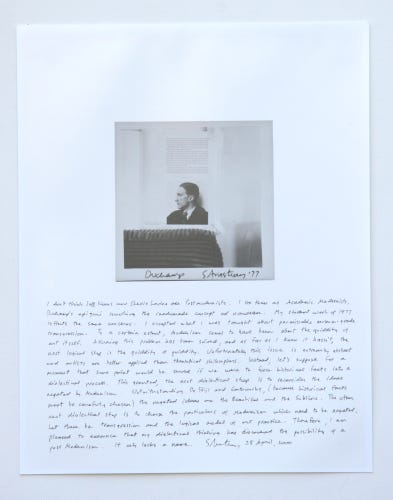

In 1977 I propped a book on the arm of a chair. It was open to a photograph of Marcel Duchamp taken by Alfred Stieglitz and I photographed it. It seemed like the perfect readymade. I then signed and dated the photo. My photo is polluted with context: the image, the book and the chair in my living room – frames within frames. Besides appropriation, it’s also about my sense of being on the outside, looking through a window into the art world, like watching a family dinner while standing outside in the snow. I was a recently graduated art student at the time, and sometimes art students feel that way, it’s very Dickens.

I also enjoyed signing the front – photographers rarely do that.

In 2000, I photographed my photograph and printed it on enough paper to write a screed. It was intended to be amusing like my Artist Statement from a previous post.

It says, “I don’t think Jeff Koons and Sherrie Levine are Postmodernists. I see them as Academic Modernists, Duchamp’s epigoni reworking the readymade concept ad nauseum [sic]. My student work of 1977 reflects the same concerns: I accepted what I was taught about permissible museum-grade transgression. To a certain extent, Modernism seems to have been about the quiddity of art itself. Assuming this problem has been solved, and as far as I know, it hasn’t, the next logical step is the quiddity of quiddity. Unfortunately this issue is extremely abstract, and artists are better applied than theoretical philosophers. Instead, let’s suppose for a moment that some point would be served if we were to force historical facts into a dialectical process. This granted, the next dialectical step is to reconsider the ideas negated by Modernism. Notwithstanding De Stijl and Earthworks, (because historical facts must be carefully chosen) the negated ideas are the Beautiful and the Sublime. The other next dialectical step is to chose the particulars of Modernism which need to be negated. Let these be transgression and the logical model of art practice. Therefore, I am pleased to announce that my dialectical thinking has discovered the possibility of a post Modernism. It only lacks a name.”

This definitely illustrates that I had developed some hostility towards theory.

Not much more to say. Here are three related works:

One-piece collage, 1977.

Pencil drawing, 1999.

Photograph, 2000.