In my last post, Romanticism, I settled on the term neoRomanticism. This was mostly just for fun. I subsequently realized that this wasn't a new idea for me, and I found a reference to it in an overly ambitious and academic 1995 essay I wrote for the inaugural issue of my magazine, Wegway Primary Culture, when it was still a humble, photocopied zine. The essay was called, “The Work of Mechanical Reproduction in the Age of Art”, an inversion of Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay, ”The Work of Art in the age of Mechanical Reproduction”.

I was happily writing 10,000 words of dense, academic, jargon-filled, theoretical speculation formatted like Immanuel Kant’s critiques while putting the names of all people mentioned in bold type so it catches the eye as if it were an article about famous people found in grocery store check out magazine.

Why did I do this? I do not know, I guess it was a secret gesture, or a private joke. Perhaps I felt lonely. Where are all the other people with interests similar to mine?

Sadly, it may have been an MA thesis written for no-one, an impossible piece of self-expressive conceptual art. I was a reader of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Bergson, and Jung in the 1980’s university atmosphere of Anglo-American analytical philosophy in the Philosophy department, and Continental Philosophy in the English department. This essay needs a rewrite in normal English.

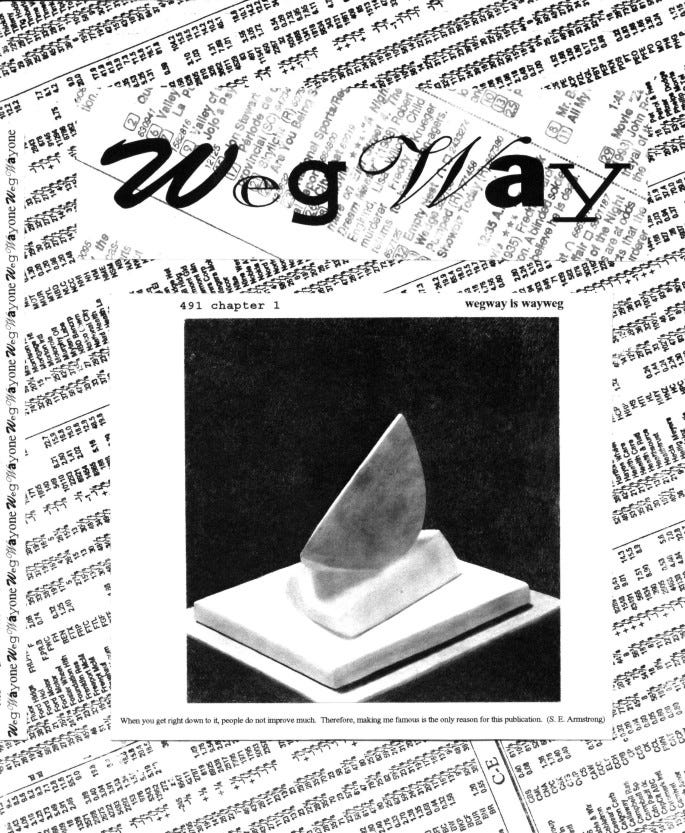

The image above is the front cover of Wegway #1 that includes a pencil drawing I made of a Barbara Hepworth sculpture in 1977. Hepworth’s piece really didn't impress me very much at the time, but I sure liked the photograph of it. I found it in a book called Circle.

Unlike art students in previous times who used statues for life drawing practice, I didn't learn anything about anatomy by drawing sculptures by people like David Smith, Vladimir Tatlin, and Barbara Hepworth. But I was certainly on the trail of something.

Maybe I was circling the work of mechanical reproduction in the age of art, or maybe, since I thought the idea of self-expression was both pointless and impossible, I was looking around for a respectable reason to draw anything at all. I was suffering from Modernism.

The essay was broken into sections with precise but somewhat impenetrable titles. There’s nothing like mixing the jargon of Kant and Aristotle/Marx in the same phrase to clarify things. I guess this is what happens when a semi-autodidact self-publishes without any input from colleagues.

First a note: A noumenon is the famous “thing-in-itself”, it's the object of our perception independent of our perceiving it. A phenomenon, on the other hand, is our perception of the thing-in-itself and we have no way to know how similar these two things might be. For example, the appearance of a tree might be very different from what a tree actually is. A quantum physicist could probably confirm that.

And a second note: A problematic, here used as a noun of sorts, is a term in Aristotelian logic. A problematic proposition is one that asserts that something is possible, such as, “It is possible that it will rain”. To ensure accuracy, this definition comes from Antony Flew’s A Dictionary of Philosophy.

The essay quoted below was written a long time ago, but I suppose I intended the term ‘problematic’ to be slightly pejorative in a manner similar to the fancy pejorative ‘putative’. To my ear, putative has a sharper edge than its close synonyms like supposed or reputed - there’s all that suspected expertise lurking in the background of someone who would use a word like putative.

Here’s the quote:

The Supposition of art’s non-particular noumenal existence is a major component of the art problematic we live in.

Epistemology is the start of philosophy and art is the stop. Art is philosophy that includes death. Like the epistemology problematic, the art-object problematic is something we remain immersed in. Not even the Marxists have escaped. I think this is because they have, as Hegel had, a facile epistemology. Marxism allows for ‘scientific’ knowledge by way of ‘theory’. Thus they are predisposed to accepting the existence of concrete particular things on nothing more than the inadequate proof of necessity. Necessity works for ideas but it does not work for things. For most of us, a noumenal art object will slip into being like the silver lining in a cloud of thought. Considering art in general leads to the presupposition of art, the thing. It certainly doesn’t entail it.

Think for a moment of Clement Greenberg. He distinguished avant-garde from kitsch, and he traced the progress of the various arts as they categorized themselves in their act of becoming Modern. Greenberg tells us that Modernism begins with Kant. Some would agree with him, and some would disagree. All the same, this is one of those misleading questions that is both big and irrelevant - Is Romanticism Modern? It is irrelevant because it leads us to believe that it is about culture when in fact, it is only about terminology. It is big because it wants to define an historical category.

There is no shortage of writers to tell us amazing things about art, and we seriously listen to these amazing things whenever we lapse into the belief art is more than a concept. Considering art as ineffably real makes us feel as if we were getting a grip on the big picture: we feel pre-epiphanic, that we were approaching something Platonically archetypal. What we do not notice in these exalted moods is that art-concepts are invariably surreptitious historical concepts and besides this, art-concepts seem to refer to some sort of art-thing that we desperately want to know about. My warning is: If you love art, and it becomes historicized for you, then you are at the dangerous gates of nihilism. Words are never enough of what we want. Talk leads to despair.